Vol. XI, No. 3, April-June 2011

- Editor's corner National Restaurant Association Show experience

- The paradox of choice and the cannibalization phenomenon

- Foundations Entertainment University July 19-21, Chicago

- How people decide where to visit

- Word-of-mom with Power Moms

- Randy White to give keynote at DNA Conference in London

- What forms our memory of a visit to an LBE?

- Club Liko in Cairo, Egypt under construction

- The trend of decreasing attendance with higher prices

- New restaurant startup book

- Current projects

What forms our memory of a visit to an LBE?

The myth that first impressions are important is wrong. It's all about the peak-end rule of memory.

There are many myths in the out-of-home entertainment and leisure industry, ones that unfortunately prevent operators from optimizing both the guest experience and guests’ memories of their experience. One is, “First impressions count.” This often leads operators to spend excessive money and management effort on the design of the first impression when entering the venue, both on the physical environment and operations. Think of the Walmart greeter as one example.

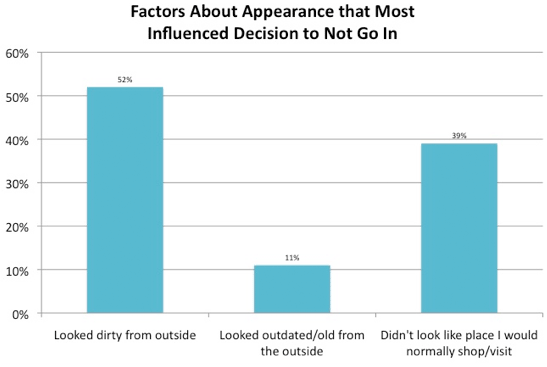

There is not question that first impressions are important. The attractiveness of the parking lot and the building can easily determine whether non-customers have a positive or negative impression of the business, determining whether they might give the business a try. A recent study in the retail industry by Morpace Omnibus, a market research firm, shows that a negative impression of the external appearance of a business will have consumers avoid it. More than two-thirds of consumers said they avoided visiting a business for the first time based on its external appearance. One-half (52%) said they avoided a business all together because it looked dirty from the outside. One-third chose not to enter a business because it “didn’t look like a place I would normally shop.” Although those consumers couldn’t specify specifically why they didn’t want to shop there, it was something about the appearance that gave them pause (a mismatch to their socioeconomic-lifestyles could easily be a factor).

First impressions can also set the mood of entering guests. However, the saying first impressions count seems to imply that it creates the lasting impression of the visit after the guest has left.

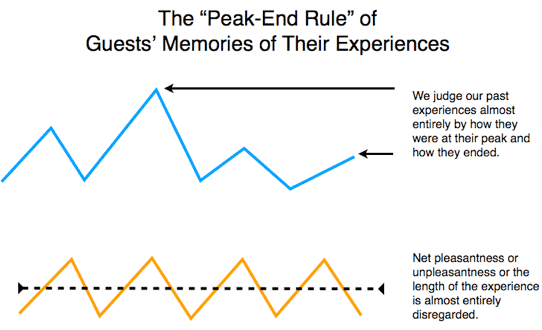

A large body of research in the field known as behavior economics tells us first impressions aren’t really important in how people remember an overall experience. Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman’s research first reported on what is called the “peak-end rule,” which shows what we remember about the pleasurable (or unpleasureable) quality of an experience is determined almost entirely by two things:

- How we feel when the experience is at its peak (good or possibly bad), and

- How we feel when the experience has ended.

We rely on these two-part summaries to remind us of how we felt about experiences. The summary is the one we remember. It’s a memory shortcut the brain uses.

When we recall an experience and how it made us feel, it turns out that its overall length isn’t terribly important. The most frequently cited study on this was on patients undergoing the painful procedure of a colonoscopy with either little or very light sedation who were subjected to a few extra minutes of lesser pain at the end of the procedure. Overall, those patients rated the experience as less painful and less unpleasant than others, even though they had been in pain longer. Other studies have found similar results for stimuli like watching film clips of playful puppies and soothing landscapes — a pleasant experience isn’t recalled later as more pleasurable just because it lasts longer.

When we recall an experience and how it made us feel, it turns out that its overall length isn’t terribly important. The most frequently cited study on this was on patients undergoing the painful procedure of a colonoscopy with either little or very light sedation who were subjected to a few extra minutes of lesser pain at the end of the procedure. Overall, those patients rated the experience as less painful and less unpleasant than others, even though they had been in pain longer. Other studies have found similar results for stimuli like watching film clips of playful puppies and soothing landscapes — a pleasant experience isn’t recalled later as more pleasurable just because it lasts longer.

What matters far more is the intensity of sensation, whether it’s excitement or pain or contentment. And it’s not the overall average of the experience that people remember, but how they felt at the most intense moments, combined with how they felt right as the experience ended. Thus, the “peak-end rule.”

So what really matters about the memory of visiting an entertainment venue is the intensity of the experience at its peak combined with what guests experience at the end, rather than the first impression. Even if a minor part of the experience isn’t a good one, people may not remember that part if the peak was good and fun and the visit ended happily.

Usually offering a great peak experience isn’t a problem for well-managed location-based entertainment venues. The main attractions themselves, such as laser tag, go-karts, bowling or Ballocity, offer a good peak experience. More often, it’s the end of the visit that’s the problem. If the end of the experience is a stop at the redemption counter on a busy day, it can make for a frustrating and unpleasant end experience. If children are involved, they often feel rushed, the counter is crowded so they can’t roam back and forth to study the prize selection, and for young children, they can’t see over the counter. And the worse it gets for the children, the more their parents are frustrated and annoyed. Re-engineering the experience with a redemption store design can overcome these problems and create a good end experience. If the last part of the visit is dining, that perpetual wait for the check when the waitperson seems to disappear can leave a bad last impression. Here, staff training becomes critical. The end of birthday parties can also be unpleasant if the experience is not properly engineered. Entertainment venues need to focus on assuring that the end of guests’ visits are a good experience to assure an overall positive guest impression and pleasant memory of the visits.

Usually offering a great peak experience isn’t a problem for well-managed location-based entertainment venues. The main attractions themselves, such as laser tag, go-karts, bowling or Ballocity, offer a good peak experience. More often, it’s the end of the visit that’s the problem. If the end of the experience is a stop at the redemption counter on a busy day, it can make for a frustrating and unpleasant end experience. If children are involved, they often feel rushed, the counter is crowded so they can’t roam back and forth to study the prize selection, and for young children, they can’t see over the counter. And the worse it gets for the children, the more their parents are frustrated and annoyed. Re-engineering the experience with a redemption store design can overcome these problems and create a good end experience. If the last part of the visit is dining, that perpetual wait for the check when the waitperson seems to disappear can leave a bad last impression. Here, staff training becomes critical. The end of birthday parties can also be unpleasant if the experience is not properly engineered. Entertainment venues need to focus on assuring that the end of guests’ visits are a good experience to assure an overall positive guest impression and pleasant memory of the visits.

Optimizing the guest experience at the peak time and also at the end of the visit will result in guests being the happiest and having fond memories of the visit, essential for positive work-of-mouth and repeat business.

Vol. XI, No. 3, April-June 2011

- Editor's corner National Restaurant Association Show experience

- The paradox of choice and the cannibalization phenomenon

- Foundations Entertainment University July 19-21, Chicago

- How people decide where to visit

- Word-of-mom with Power Moms

- Randy White to give keynote at DNA Conference in London

- What forms our memory of a visit to an LBE?

- Club Liko in Cairo, Egypt under construction

- The trend of decreasing attendance with higher prices

- New restaurant startup book

- Current projects