Vol. X, No. 7, November-December 2010

- Editor's Travelogue

- The great FEC theming myth

- Hamburgers still king of sandwiches

- What's next: the future is already here

- Randy's blogging

- Managing prime food and beverage costs for maximum profitability

- The challenge of designing environments for families with children

- 2011 Foundation Entertainment University dates

- The culture of eating occasions

- Current projects

Managing prime food and beverage costs for maximum profitability

Food and beverage is an essential component of offering guests a good experience, one they’ll want to repeat. A location-based entertainment (LBE) facility with a well-executed food and beverage (F&B) offering will not only increase per capita F&B sales (sales per guest per visit), but will also increase other sales by extending the guests’ length-of-stay. In fact, F&B can actually be a driver of visits — come for the food and stay for the fun.

As important as F&B is to the guest experience equation, it is just as important to profitability. When it comes to F&B profitability, revenue is only one part of the equation. The other part of the F&B profit equation is prime cost. LBEs have the potential to achieve per capita F&B sales of $5 or greater. With properly managed prime costs, F&B sales can add $2 in profit for every guest.

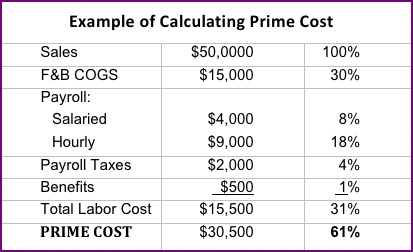

Prime cost is the total cost of goods sold (COGS). That includes food, beverages and related paper products such as disposable cups, napkins, etc., plus the gross labor cost for all F&B staff. Labor cost not only includes payroll, but payroll taxes, worker’s comp, medical insurance and other employee benefits. For a foodservice facility, a good benchmark for prime cost is 60% or less of F&B revenue. This means the total cost of food, beverage, associated paper goods and all labor costs should not exceed 60% of revenues.

It is important to track prime cost on a regular basis, as it includes the two most controllable costs — labor and cost of goods sold. However, we often find that LBE operators:

- Don’t track labor costs separately for F&B, but rather lump all labor together for their entire facility, or

- Track labor as a percentage of F&B sales only on a monthly or less frequent basis, or

- Rarely track F&B COGS except on an annual basis.

The problem with such infrequent tracking of prime cost is that months can pass before the operator recognizes that costs may have exceeded the target benchmark. There’s no way to go back and correct costs at that point, so it represents a permanently lost profit opportunity. For example, maybe the costs of some raw products have increased and driven up food costs. If you wait for months to find out, then you’ve lost the opportunity to either adjust menu prices or find less expensive substitute products. Perhaps some new employees haven’t been properly trained and aren’t following proper portion control. Maybe your F&B manager hasn’t been efficiently scheduling employees. Waiting a month or longer to find out that labor costs are 40% instead of 30% means your costs have been higher than necessary. Or perhaps an employee has been stealing some food product out of your walk-in on a regular basis. Waiting months to calculate COGS to finally learn things are out of kilter can mean you let thousands of dollars walk out the back door (literally).

When it comes to labor costs, we recommend that its percentage of revenue be calculated daily. Yes, that’s right, daily! It isn’t that hard to set up your bookkeeping system to do this. Each morning, the F&B manager gets a report on what the labor percentage was for the previous day. That gives the F&B manager the opportunity to learn how to improve through immediate feedback. If you wait weeks or months to give her this information, she will have forgotten what happened on particular days in terms of scheduling to cause the high labor cost. If she gets a report the next morning, however, she can reflect on the previous day and perhaps learn what she can do differently to improve the labor percentage in the future.

The other advantage of daily reporting is it sends a loud and clear message to your F&B manager that controlling labor cost is darned important. The old adage, “That which gets measured gets attention,” is very true. Labor is your most easily controllable cost, so it only makes sense to set up a reporting system that helps your managers stay focused on controlling it.

Calculating the COGS part of prime cost also needs to be done on a frequent basis. Most chain restaurants do it weekly. At a minimum, it should be done bi-weekly. Weekly or bi-weekly cost reporting will change the attitudes and behavior of your kitchen staff, as it creates awareness of the importance of controlling F&B costs. It also lets employees know they are being held accountable. If there is a problem, you will know about it quickly and can respond accordingly. Regular food costing will usually result in a 2% to 4% or more reduction to COGS. Again, that which gets measured gets attention.

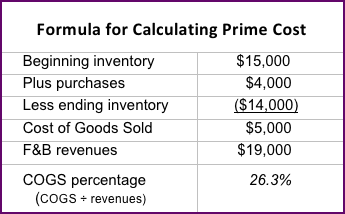

Calculating COGS requires a physical inventory of all F&B supplies on hand and a calculation of their costs. This takes some time, but with a well-organized stockroom and by setting up simple inventory worksheets, a physical inventory can easily be done in an hour or so. Conducting regular physical inventories also requires the discipline of setting a fixed scheduled time for it.

The following chart shows the formula and provides an example for calculating COGS for any time period:

When auditing the operations of many of our LBE clients, we often discover their menu prices have not been appropriately calculated to produce desired profit margins. We frequently find COGS running 40%, 50% or greater of their F&B sales.

We often find that clients have priced their menu items under the market for similar type restaurant operations, sometimes for even less than McDonald’s sells those items. You should never price your menu items cheaper than comparable restaurant prices. Menu prices that are too low can actually hurt sales, as guests will be suspicious that the food quality is low, based on the price. Actually, with good quality products and display cooking, such as preparing foods right in front of customers, you can command a premium price over comparable restaurant operations. The public looks at it as more of a value equation than just an absolute price consideration when purchasing quality prepared foods.

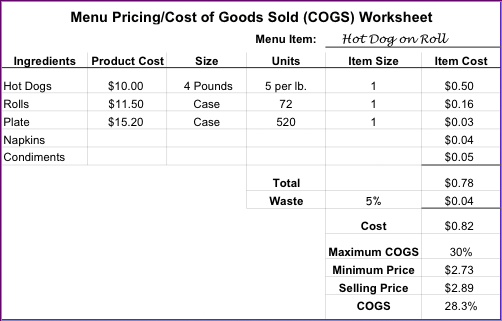

Properly setting menu prices requires a detailed cost analysis of each menu item, making sure the cost includes every ingredient and paper product used for that item. For example, for a hot dog, the cost analysis should include not only the hot dog and roll, but also the cost of condiments, the paper plate and napkins. Then a factor needs to be added for waste — food that spoils, dropped food that is thrown away, and prepared left over food that can’t be saved at the end of the day. Then, you take the total cost of the menu item and divide it by your desired COGS. Let’s say the total cost of the gourmet hot dog works out to $0.76 and you want to maintain a COGS of 30%. You divide $0.76 by 30% to get the target-selling price of $2.54. But you don’t stop there. If hot dogs of a comparable quality are selling for $2.89 in your market, you set the price at $2.89, which gives you a 28% COGS. A worksheet for this example is shown below.

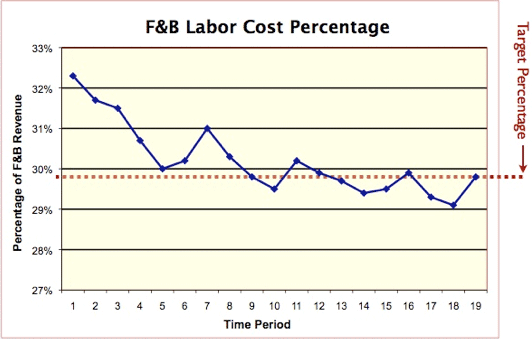

We have found that in addition to supplying labor costs and COGS to your F&B manager, taking an open-book approach of sharing this information with all F&B staff greatly improves performance. We advise our clients to post two graphs where the F&B staff will see them everyday. One can show the weekly labor percentage and the other the weekly or bi-weekly COGS. The vertical axis should show ascending percentage and the horizontal axis should indicate the time periods. The target range should also be shown. Then, each day or week, the new results are posted. This gives the staff immediate feedback on performance. First, if the percentage is in the target range, that is good. Secondly, if the graph shows costs going up, that tells employees things are moving in the wrong direction (increasing percentage). If the percentage on the graph is going down, that means the staff is improving (decreasing percentage).

The open-book approach sends the message to all F&B staff members that controlling prime cost is important. It gives them immediate feedback on how they are performing. Staff members have far more control of COGS than anyone else, because they handle portion control. They create waste. They are doing (or not doing) the up-selling to more profitable food items. The graphs will help them understand why proper portion control, minimizing waste and up-selling are so important. It lets the F&B staffers know they’re regularly being evaluated in these performance areas. It also lets them know that if they steal, their theft will quickly show up in the performance results. And if their hours need to be cut back, they can better understand why -- that it is necessary from a business profitability standpoint and is not some arbitrary management decision.

Controlling prime cost requires commitment, procedures and discipline. When executed properly, you will have a continuous stream of profits from your food and beverage sales.

Vol. X, No. 7, November-December 2010

- Editor's Travelogue

- The great FEC theming myth

- Hamburgers still king of sandwiches

- What's next: the future is already here

- Randy's blogging

- Managing prime food and beverage costs for maximum profitability

- The challenge of designing environments for families with children

- 2011 Foundation Entertainment University dates

- The culture of eating occasions

- Current projects