Vol. XVII, No. 8, December 2017

- Editor's corner

- More about the appeal of LTOs

- Unpartnered share of Americans on the increase

- Meet the conscientious consumer

- Ocean5 and Table 47 about to raise the bar

- A shrinking young adult market

- The importance of great designed spaces

- Out-of-home entertainment expenditures on the increase

- It's no longer about entertainment; it's all about the experience

- The marriage of food and entertainment

- Outdoor attractions are solid FEC profit centers

- Wake up at dawn to dance at this new rave

- Households with children on a downward slope

- New CLVs worth noting

Meet the conscientious consumer

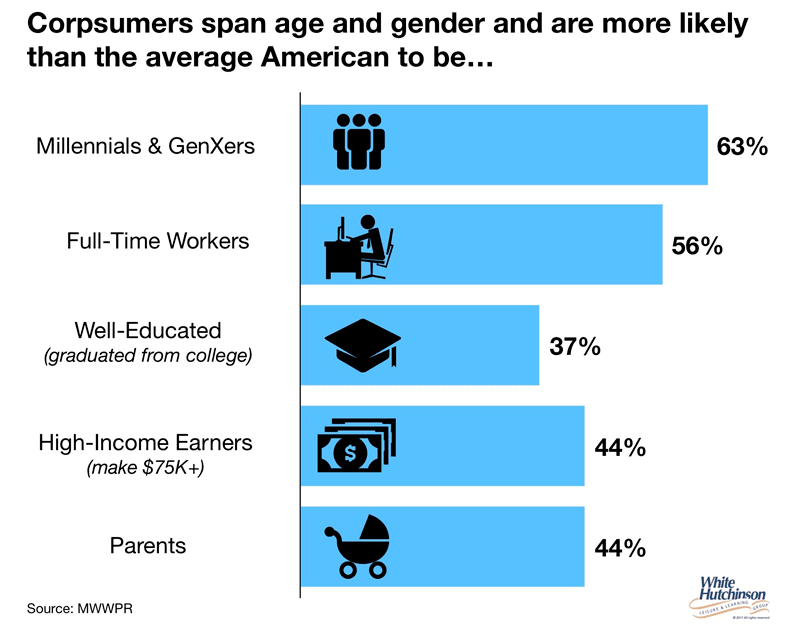

A significant shift in consumer values has created a new consumer segment identified as corpsumers by MWWPR, a public relations firm. Corpsumers represent one in three Americans ages 18 to 80. At 80 million, they are a population larger than Millennials and larger than moms. They cross all ages, demographics and geographies. Corpsumers are more likely to be Millennials and Gen-Xers, full-time workers, well-educated, high-income earners and parents.

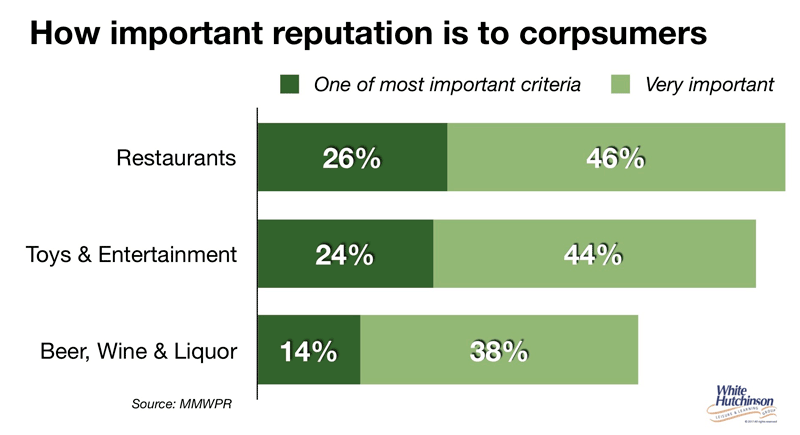

Corpsumers believe a company's values, actions and corporate reputation are just as important as the products and services it offers. They practice what is often called “ethical consumerism” or “conscientious consumerism,” the practice of purchasing products and services from companies that actively seek to minimize social and environmental damage and the avoidance of products and services that have a negative impact on society or the environment.

Although 75% of Americans agree strongly or fully that a company's reputation is just as important as the products or services it offers, corpsumers act on their beliefs. They walk the talk with their wallets by supporting a company's values and actions they believe in by purchasing its products and services.

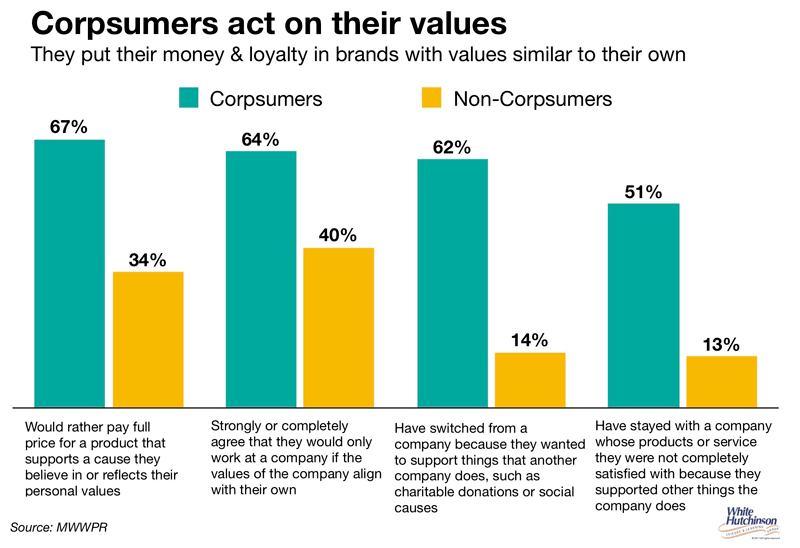

Corpsumers are more loyal, less price-sensitive and more vocal than most Americans about the brands and companies they believe in and support. Over half of corpsumers (51%) have stayed loyal to a company that they believe is trying to do the right thing even if they weren't satisfied with its products or services. Two-thirds of corpsumers (67%) would pay full price for a product that supports a cause they believe in or reflects their personal values rather than buying a product at a discounted price from another company.

Carreen Winters, Chair Reputation Management and Chief Strategy Officer at MWWPR, explained it this way. “A few things have changed. In the past, we defined as “good” in the absence of the company doing anything wrong. Today, corpsumers actually investigate and seek out information in a desire to see if the company is worth doing business with. And the information they seek isn't just about the product, but their behavior. Consider Starbucks. They provide education and healthcare benefits to all of their employees in a way that is truly unique and defines them as a good employer. Many corpsumers are loyal to Starbucks in large part because of the “goodness” of the company and are willing to forgive their missteps - like their “Race Together” flop. They are also willing to pay a premium for a brand's products that support causes they believe in - which was validated by our research.”

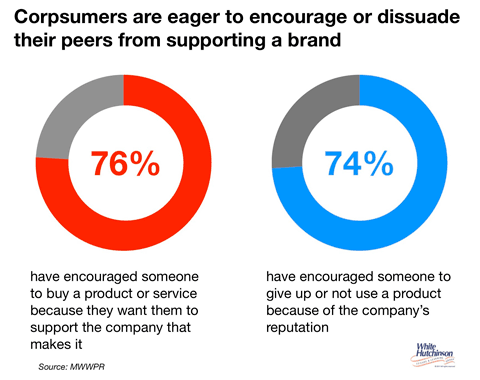

Corpsumers are brand activists. They pride themselves on influencing their friends and families and using their social media channels to broadcast their support or disapproval of companies and urge their followers to act accordingly. Three quarters (76%) have encouraged someone to buy a product or service because they want him or her to support the company. Three in four (74%) corpsumers have encouraged someone to give up or not use a product because of a company's reputation. The vast majority (89%) is likely to share positive news about companies and over three-quarters (78%) are likely to share negative news about companies.

Elizabeth Currid-Halkett, author of The Sum of Small Things, has identified a rising new class in America that has characteristics very similar to corpsumers. She says a new cultural elite consumer is on the rise that she calls the aspirational class; people who aren't necessarily rich or defined by their incomes, but defined more by their higher educations and cultural capital, who share a set of believes on the most socially conscientious ways to spend money that becomes a significant part of their identity and social capita. The aspirational class is basically the top 20% to 25% socioeconomic of the population.

Currid-Halkett sees these consumers as driven primarily by an aspiration to acquire knowledge and to use that information to form socially and environmentally conscientious values and behaviors that set them apart and at least makes them appear to be - “their versions of better humans.” Part of aspirational class consumerism is rooted in the value of “conspicuous production” - transparency in production and processes and a premium on locally sourced and socially conscientious farming and manufacturing that justifies the expense and is inherent to the value of most of the consumer goods and services they purchase. That is why for them, a $2 heirloom tomato or free-range chicken purchased from a farmers market is symbolically significant.

The aspirational class has a clear moral compass. They worry about climate change and personal dignity, they want to preserve regional and local identity, they are concerned about their children's and the planet's future. They aspire to limit their carbon footprint, go “green”, buy organic and sustainable products, make sure the origin can be traced and that labor used to make them has not been exploited. In short, they “aspire” to be better human beings and politicize their social conscientiousness and environmental awareness through their consumer choices, which acts as a signal of their philosophy of life and their value system and becomes part of their social capital.

MMWPR and Currid-Halkett are not the only ones finding that consumers expect brands to not only have functional and pleasurable benefits, but also a social purpose, and that a significant segment of those consumers are activist ethical consumers both with their wallets and word-of-mouth.

- 57% of consumers surveyed by the 2017 Earned Brand study said they are either buying or boycotting brands based on the brand's position on social or political issues. This was up 30% from just three years ago.

- The Hartman Group's Sustainability 2017 report found that over one-third of Millennials (35%) feel their purchases have a bigger impact than their political votes, suggesting they are very serious about the significance of their purchases.

- The Sheldon Group's Millennial Pulse 2017 Special Report found that two-thirds of Americans (68%) say a company's corporate social responsibly activities positively impact their purchase decisions, up from one-third (35%) just two years ago.

- A January 2017 survey by CivicScience found that 36% of consumers say a company's social conscientiousness is very important in choosing where to shop and what to buy. That was a one-quarter increase from 29% in October 2016, right before the November election.

- The October 2017 Conscious Consumer Spending Index survey found that 61% of Americans feel that it is important to buy from socially responsible companies and over one in four Americans (27%) reported spending about half their money on socially responsible products and services. 30% said they plan to increase their spending with socially responsible companies in the year ahead. The 2016 survey found that 45% of Americans say buying/using eco-friendly products is an important part of their personal image and one-quarter said they did not purchase goods or services because the company was NOT socially responsible.

- LOHAS (Lifestyle of Health and Sustainability) is a market segment of consumers who actively seek out healthier and more sustainable and socially responsible lifestyle, products and service options. They are not defined by their age or gender, rather instead by their values. LOHAS consumers' lifestyle and purchasing decisions are motivated by their values regarding personal, family and community health, environmental sustainability and social justice. Currently one in four Americans identify as living a LOHAS lifestyle.

Today, a large segment of consumers, including those belonging to the corpsumer and aspirational class, increasingly view corporate responsibility, from organic ingredients to animal welfare to company treatment of employees to sustainable practices as aspects of quality, not just a “feel-good factor.” In fact, they often consider purchasing products or services from an ethical company as a luxury and as a status symbol. For them, the idea of luxury is defined far less by expensive possessions than by a set of cultural values. Terms such as organic and sustainable are now used to convey a sense of high-value luxury. Currid-Halkett's theory is that “social, environmental, and cultural awareness” have become the new social capital. She says that because most consumer products are now widely available, all but the most exclusive items have lost their value as class signifiers. In their place, goods and services, what she calls conspicuous leisure and inconspicuous consumption that broadcast a consumer's high education levels and cultural awareness to their peers have gained importance, such as organic produce and yoga classes. Sustainably made goods work as status symbols. Ordering a grass-fed organic hamburger is now both a luxury, as well as something that will gain you social capital among your peers.

This significant shift in consumer culture means that social good has become the new cool. Whether you call them corpsumers, ethical consumers, conscientious consumers, socially-conscious consumers, the aspirational class or LOHAS, the segment of consumers that now link their wallets' purchasing power and their word-of-mouth and eWOW to good citizen companies and their products and services is today a significant consumer force that any consumer company needs to understand and address. What it means is that just having a great product or service, including entertainment, is no longer sufficient to succeed today. What a company stands for, its purpose and its social, ethnical and environment actions, its social accountability, has now become integral to its products or services functional benefits that factor into the decision of whether to purchase or not for a large part of the population. There is now a blurring of the lines - people are blending their consumer choices and their beliefs and values into one. This blending of consumerism and social conscientiousness has created expectations about how products are grown and made, how employees are treated and how the environment is impacted.

In marketing, it used to be about the four Ps - price, product, promotion and place. Now with the conscientious consumers it needs to include a fifth P - purpose. Companies today need to be more than about profit. Consumers expect companies to have a higher-order purpose that they practice and make transparent - they want to know what companies are doing to make the world a better place.

This means that companies need to tell the stories about their purpose and its practices as much as, if not more than they tell their product or service stories. And those purpose and practice stories need to be authentic and real.

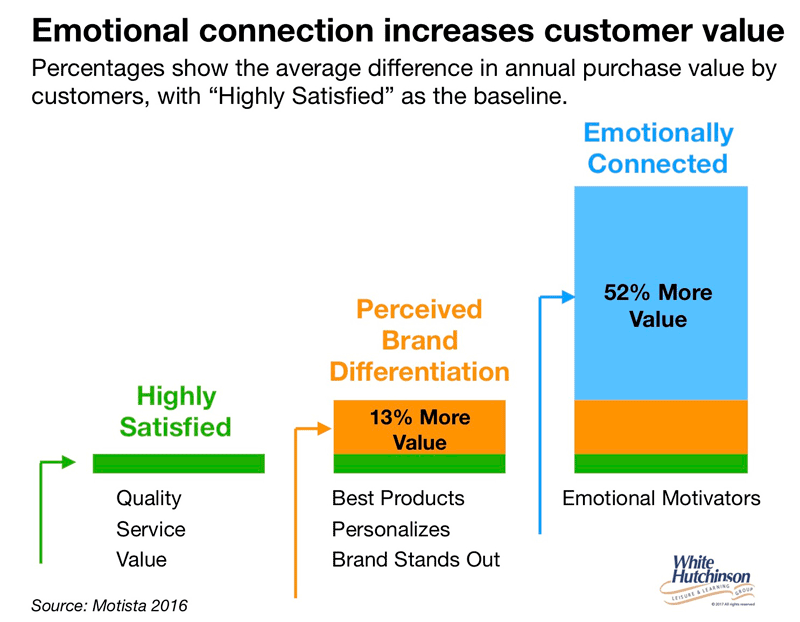

Environmentally responsible companies have the opportunity to connect with conscientious consumers' emotions and increase their value to the company. Motista, a consumer intelligence firm, has identified hundreds of emotional motivators that connect with consumer feelings and drive their behavior. One of the more significant ones that inspire a large segment of consumers, the conscientious consumers, is the desire to protect the environment. Motista defines that emotional motivator as helping consumers “sustain their belief that the environment is sacred; to take action to improve their surroundings.” Motista found that consumers are emotionally connected with a brand or company when it aligns with their emotional motivations and helps them fulfill those desires. Their research found that fully connected consumers are 52% more valuable on average that those that are just highly satisfied; their value is strikingly higher for both spending and frequency. In the hospitality industry, there was a 41% increase in value for stays at hotel.

Implications for CLVs

Acting socially and environmentally responsible and creating a positive social impact on society and the world is no longer optional for businesses - it is now a basic requirement for success based on the increasing importance many consumers place on making a difference by the companies they choose to do business with.

The rise of conscientious consumerism is something that the majority of entertainment-oriented community leisure venues (CLVs) have ignored. Some restaurants (one of CLV's segments) are starting to embrace it with farm-to-table, organic, LEED facilities and fairer worker compensation, but even they are a small segment of the restaurant industry.

The vast majority of conscientious consumers belong to the highest educated Americans, mostly Millennials and Gen-Xers, including the ones with families with children. They account for around 70% of all spending at entertainment-oriented CLVs, including at FECs, bowling entertainment centers (BECs) and the fast growing adult-focused social eatertainment venues. They are the target market that defines success in the CLV industry. Just like there are now so many consumer choices for goods, the same is now true for entertainment and out-of-home experiences, more specifically, all the different options consumers have for their leisure time - far more than they can ever hope to enjoy. Social and environmental responsibility has now become a defining factor for conscientious consumers in the choices they make about which companies they do business with. That is now becoming true for CLVs. This means that it is now important for success to not only offer a great entertainment, fun, food, beverage and social experience, but also increasingly important to run a CLV business that is socially and environmentally responsible. We are now at the tipping point where not being a responsible CLV will start to negatively impact business.

Millennials and Gen-Xers rank very high on being ethical consumers. They, along with members of other generations who are ethical consumers, want these qualities in socially responsible companies:

- Companies to be actively invested in the betterment of society and the solution of social and environmental problems

- Companies that prioritize “making an impact” on the world around them

- Companies that are open and honest - transparent about their pro-social and sustainability initiatives

- Companies that give their customers the opportunity to be involved in their good works. Ethical consumers want an opportunity to give back - whether it's with a gift of their time or their money

Vol. XVII, No. 8, December 2017

- Editor's corner

- More about the appeal of LTOs

- Unpartnered share of Americans on the increase

- Meet the conscientious consumer

- Ocean5 and Table 47 about to raise the bar

- A shrinking young adult market

- The importance of great designed spaces

- Out-of-home entertainment expenditures on the increase

- It's no longer about entertainment; it's all about the experience

- The marriage of food and entertainment

- Outdoor attractions are solid FEC profit centers

- Wake up at dawn to dance at this new rave

- Households with children on a downward slope

- New CLVs worth noting