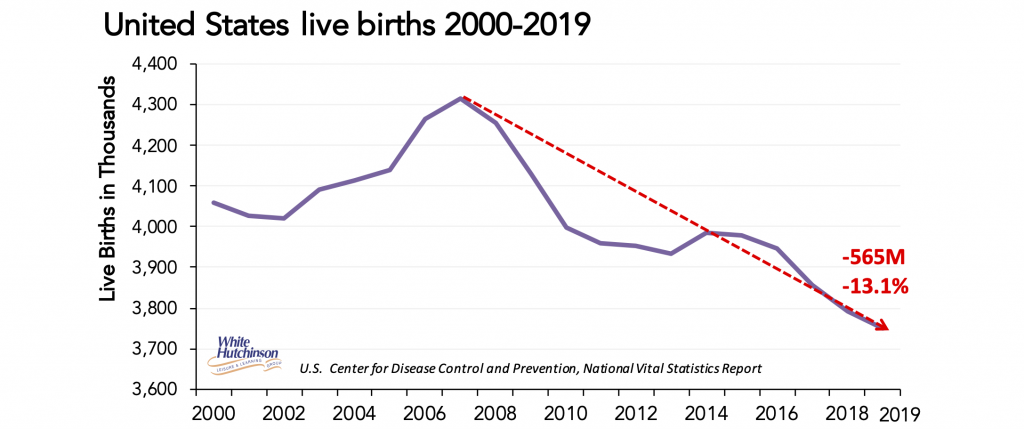

The baby bust that started back in 2008 continued through 2019 with 42,000 fewer births, a 1% decline from 2018. In 2019, there were 565,000 less births than back in 2007, a 13% decline.

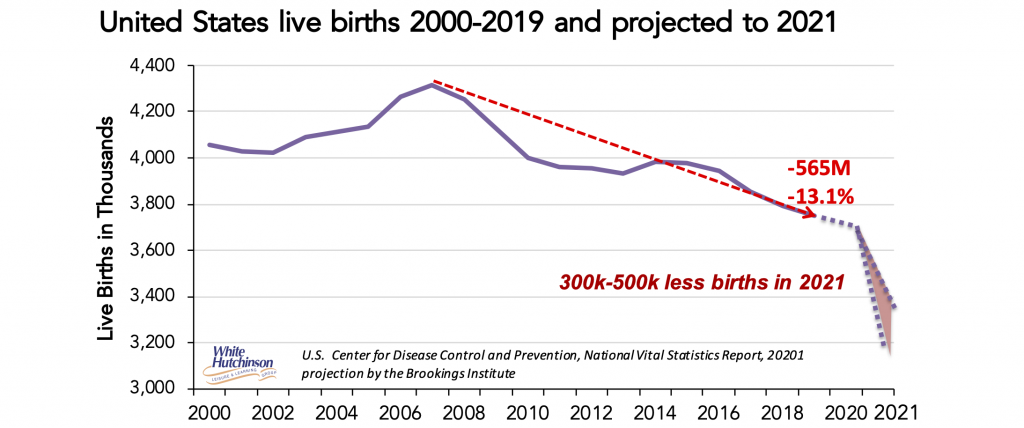

If you thought all the people stuck at home with their romantic partners during the lockdown and/or self-quarantining would reverse the trend and lead to a baby boom, you are probably wrong based on the lessons from history and what researchers are predicting. Rather than a boom, analysis by researchers at Brookings say we can likely expect a “large, lasting baby bust.” The researchers estimate that the economic downturn caused by the pandemic could result in a dramatic decline in births. They reached that conclusion from studying the fertility decline of the Great Recession and the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic impact on births.

The researchers also examined previous studies that found when there is a recession with a reduction in employment and earnings, there was a reduction in births. Those previous studies found that a one percentage-point increase in the unemployment rate is associated with a 0.9% to 2.2% decrease in birth rates. An analysis of the Great Recession’s impact on births led the researchers to predict that women will have many fewer babies in the short term, and for some of them, a lower total number of children over their lifetimes.

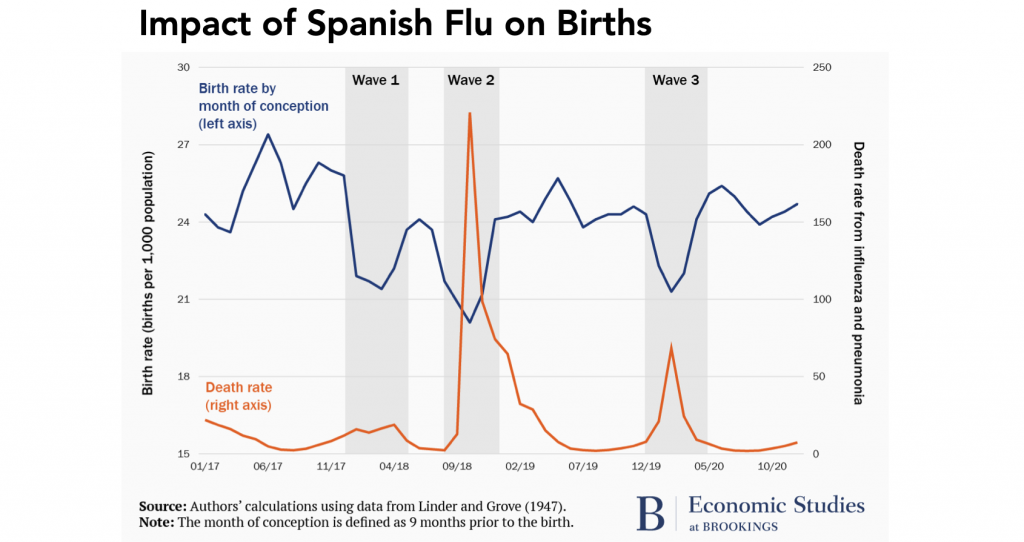

The 1918 Spanish Flu is a good comparison to the current pandemic, as it was a widespread and severe pandemic. The Brookings research found that spikes in death rates led to large declines in births.

The researchers found both similarities and differences with the Spanish Flu compared to the Covid-19 pandemic. The drop in births that resulted from the Spanish flu was likely due to the uncertainty and anxiety from the public health crisis, which could affect people’s desire to give birth, and also biologically affect pregnancy and birth outcomes. That could be true during this crisis as well. But, unlike what we’re experiencing today, the economy contracted only modestly during the Spanish Flu because of the economic support from the ongoing World War I effort. As a result, the authors suggests Covid-19 could have a bigger impact since the public health crisis has also hit the economy. Furthermore, they point out that women today have access to much more effective forms of contraception.

Combining the economic impact of the Covid pandemic along with its public health crisis, the researchers concluded we could see a decline in births on the order of 300,000 to 500,000 fewer births in 2021 than would normally occur.

The researchers went on to say that additional future reductions in births may be seen if the labor market remains weak beyond 2020, since the current economic circumstances are likely to be long-lasting and will lead to a permanent loss of income for many people [which economists are now predicting]. They expect that many of the births will not just be delayed, but will never happen. There will be a Covid-19 baby bust. The researchers concluded, “That will be yet another cost of this terrible episode.”

During the 1918 pandemic, there was a 10% drop in births experienced over the 9 to 10 months following the peak in deaths. Using the 2019 number of births results in 375,000 less births at a 10% decline in 2021. That is in the range the Brookings paper predicts. Births did rebound to pre-pandemic levels after the Spanish Flu pandemic ended, but as the Brookings research points out, there was only a minor economic impact during and that pandemic, as is not the case with the Covid recession.

The research’s predicted range for the drop in births in 2021 is between -8% and -13% of 2019 births. That’s a major decline. At the high range of -13% (-500,000 births), that’s equivalent to the percentage drop in births that took 12 years to occur from 2007 to 2019. It would mean more than 1.0 million less new babies in 2021 than in 2007, an overall 25% decline.

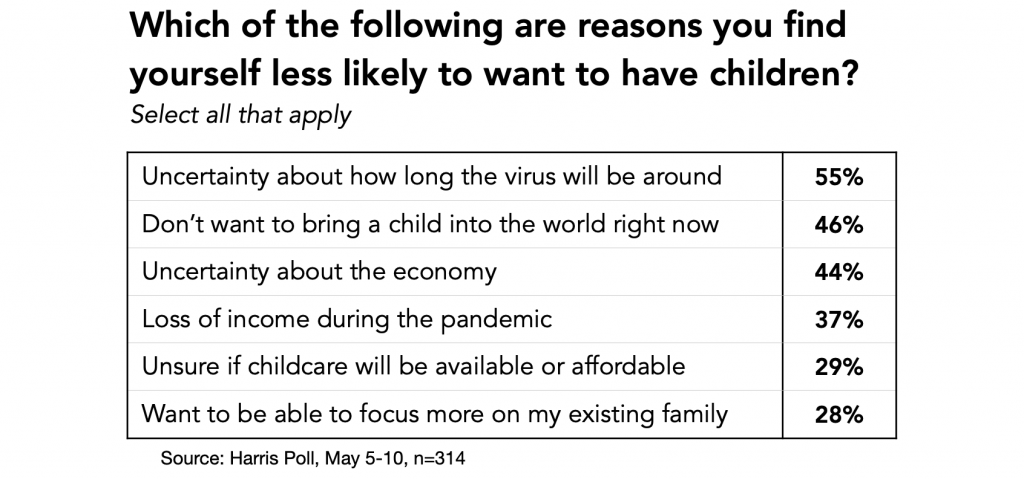

A May Harris poll indicates the predicted birth decline will be real. The poll found that 58% of adults who before the pandemic were planning to have children within the next 5 years said they were now much or somewhat less likely to want to have children due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Here’s the reasons those adults gave when selecting all that apply:

A Guttmacher Institute April 30-May 6 survey found that 40% of women reported that because of the Covid-19 pandemic, they’ve changed their plans about when to have children and how many children to have. Changes in childbearing preferences were more common among women without any children than among those with children (45% vs. 38%). Overall, one-third (34%) of women want to get pregnant later or have fewer children because of the pandemic. The percentage was higher at 37% for higher income women. In contrast, 17% of women reported they wanted to have a child sooner or wanted to have more children because of the coronavirus pandemic.

The above research and polls all came before yesterday’s announcement by The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that broadened its warning about who is at risk of developing severe disease from a Covid-19 infection. The new warning included that being pregnant may increase a woman’s risk of being hospitalized and having a severe bout of the illness, based on a study of more than 8,000 pregnant women in the United States who were diagnosed with Covid-19. However, the study did not find an increased risk of death among the pregnant women. This announcement is sure to further dampen women’s desire to become pregnant during the pandemic.

On top of the continuing decline in births that started back in 2008, the coming Covid baby bust will have major future implications for any business that caters to children and families with young children. In addition to the previous slowly declining number of births each year, now there could be a 2021 one-age birth cohort drastically lower in number than the previous year. Suddenly the potential market for baby products, and as the newborns age in the years ahead, for children products, will be in the range of one-tenth less (300,000 to 500,000 less children). That is a drastic reduction. And if the recession is long lasting, subsequent years may also see substantial reductions in births, more so than we have previously been seeing each year.

The pandemic baby bust will start impacting the attendance at location-based entertainment venues that cater to younger children starting in 2023 when the cohort reaches age 2 and then for all the following years. The decline in the size of the market for children’s out-of-home entertainment that started in 2008 will have taken a sudden dramatic downturn.